Just as I was writing about how I imagined a modern Elinor and Marianne to be, I had the chance to see a modern adaptation of Sense and Sensibility – From Prada to Nada. As opposed to rural Devon, this light comedy, directed by Angel Gracia, is set amongst the palm trees of modern L.A.

The opening scene shows two Mexican-American sisters, Nora (Camilla Belle) and Mary (Alexa Vega), out shopping designer-style. They drive into their Beverly Hills mansion, where their father is celebrating his birthday. But – as we already know – he is soon to die and the two sisters are ousted from their home, following the arrival of their (illegitimate) brother, Gabe (Pablo Cruz).

Shopaholic Mary (Marianne)

Studious Nora (Elinor)

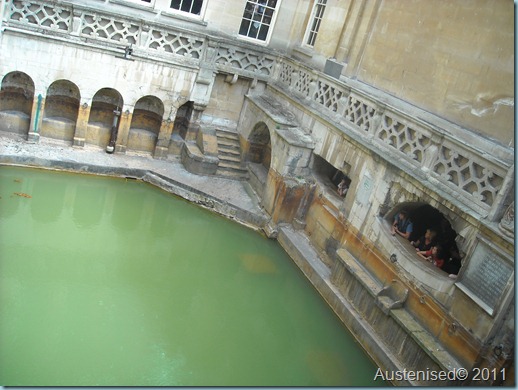

The girls find a new place to live with their aunt and other relatives, on the other side of town. You get to see a totally different side of L.A. to what we are used to seeing in films and on TV. The Mexican East L.A. is an L.A. of immigrants and the proletariat, shabby and run-down - but also vibrant, colourful, noisy and full of life.

From this setting…

…to this ‘hood.

Enter Edward Ferris (Nicholas D’Agosto), brother of her sister-in-law and a well-to-do lawyer - a less awkward version of Edward Ferrars without the imposing family connections. He soon becomes interested in law student Nora who, however, has a “10-year plan” for life and is not interested in a relationship – or so she thinks.

Nora and Edward

The younger sister, Mary, is soon swept off her feet by Rodrigo (Kuno Becker), her charming teacher of literature – love over literature, as with Marianne and Willoughby – who of course turns out to be the villain of the story.

Mary with Rodrigo

What makes this storyline less convincing is the fact that this version of Colonel Brandon, helpful neighbour Bruno (Wilder Walderrama), is actually far more charming and attractive than Rodrigo. (You might remember Walderrama from his silly role as Fez in the 70’s Show – in From Prada To Nada, however, he acts well and has plenty of charm.)

Nora with Bruno

As one might expect from a modern adaptation, the roles of the two sisters differ somewhat from the novel. While Mary (Marianne) is portrayed as snobbish and super-confident, Nora (Elinor) is the opposite - down-to-earth and hesitant. You would not describe them as ‘emotional’ vs. ‘reserved’ as you might characterise the polarities of the characters in the novel.

From Prada to Nada is a light take on Sense and Sensibility, which certainly doesn’t match up to the wit of Jane Austen. A harmless chick flick, it is a pleasant enough watch, as long as you don’t expect a mind-blowing artistic experience. After a bimbo beginning, the film does get more enjoyable towards the end, thanks to the colourful Mexican flavour – though I would have preferred having “less cheese on my nachos”!

Looking forward to seeing Scents and Sensibility next…